COP29 event raises the bar on understanding and addressing extreme heat

Photo of the speakers at the UNDRR event on extreme heat at COP29 in Baku

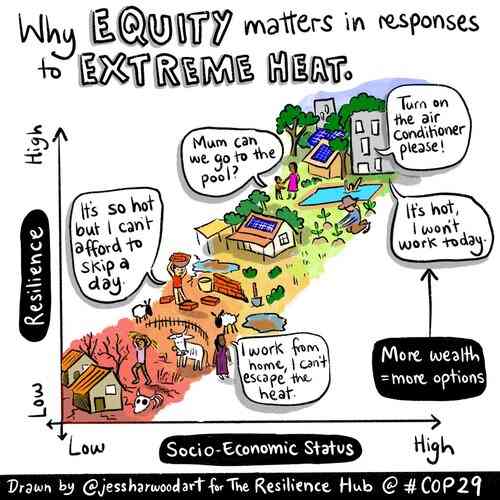

Growing instances of extremely high temperatures, for longer durations, are adversely affecting lives across the globe. As a result, extreme heat is not only deadly, but it also disrupts economies, affects multiple sectors, compromises environmental integrity, and impacts the overall functioning of societies. And while billions of people are affected by extreme heat, manifested often through heat waves, it is the most vulnerable and exposed communities that are the hardest hit.

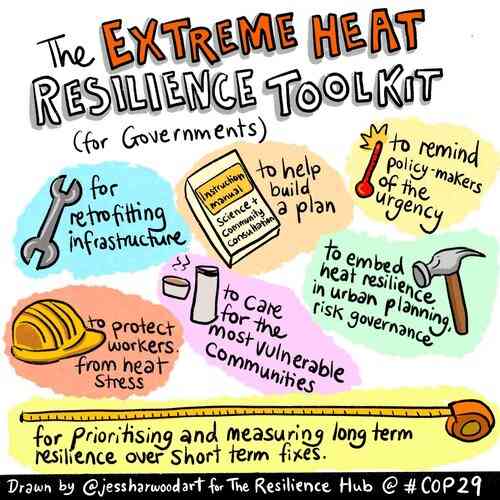

In response to this growing crisis, the UN Secretary-General has issued a global Call to Action on Extreme Heat in July of this year. It calls on the international community to act on four critical areas: Care for the vulnerable; protect workers; boost the resilience of our economies and societies using data and science, and limit temperature rise to 1.5°C.

Reinforcing this Call to Action, the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) hosted an event at COP29 to highlight actions that can enhance the resilience and adaptive capacity of countries to address the risk of extreme. The event, titled “Beyond Emergency Response: Long-Term Transformations for Extreme Heat Resilience,” was moderated by Kamal Kishore, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction and head of UNDRR, and featured contributions from Australia, Germany, ICLEI, Mahila Housing Trust in India, and the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Participants discussed the magnitude of the global challenge, its disproportionate impact on certain communities and countries, and explored means to reducing impacts through fostering multi-sectoral collaboration and promoting innovative, scalable policies and practices.

Sebastian Lesch, Head of Climate Policy at the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and a Member of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage, highlighted that extreme heat is no longer the problem of just a specific region or country, but a global issue:

“Extreme heat deserves high political attention and needs more investment. We need to better understand how this affects construction, health systems, school schedules, and transportation. We also need a layered approach to better understand the risk and look into the larger funding arrangements”, he said.

David Higgins, Acting Head of the International Climate and Energy Division at the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) in Australia, outlined the efforts taken by his country to mitigate the impact of extreme heat, which often manifests as bushfires. Pointing to the increasing awareness of the danger of extreme heat in the country, he said that “Australia has developed national climate risk assessments for 11 risks including heat. This has helped establish a heat rating system to enable impact-based forecasts as well as a national heat health action plan that helps govern heat stress better in a federal set-up.”

Higgins also pointed to progress in the development of heat maps and “cool route maps,” to help people plan their commutes, and noted the importance of international cooperation, citing as an example, Australia’s peer exchange with Singapore on addressing urban heat.

Discussing urban heat in the context of labour, Moustapha Kamal Gueye, Director of ILO’s Priority Action Programme on Just Transitions, shared recent findings from ILO that indicate that more than 2.4 billion, or over 70 per cent of the global workforce of 3.4 billion, are likely to experience excessive heat during their work. He explained the wide impact this has on workers who have to work despite heat stress, resulting in long-term health issues and nutritional impacts, or being at higher risk of job loss and reduced income.

“While we need to celebrate that for the first time, more than half of the global population is covered by some form of social protection”, Moustapha highlighted, “in the 20 countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis, only one out of 10 people have such a coverage.”

Left out of labour and occupational safety laws are people who work from home or in the informal sector, most of whom are women.

For such women, heat stress exacerbates the dual care burden of increasing economic load and worsening health, coupled with poor infrastructure. This was highlighted by Bijal Brahmbhatt, Executive Director of Mahila Housing Trust in India: “We need a community-centric model – one that focuses on ‘action’ of heat action plans - for managing heat stress in developing countries that suffer from poor infrastructure and housing.” She shared good and simple practices that can reduce heat stress for the urban poor, for instance, through measures such as cool roofs, cool shelters, cool bus stops, and micro-insurance for heat.

Emani Kumar, Deputy Secretary-General of ICLEI, cited a “Heat Wave Guide for Cities,” that ICLEI had produced with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), as a tool available to cities. He shared examples of innovative solutions to reduce urban heat stress across developing countries, such as through increasing green cover or installing water sprayers in urban parks. Kumar also stressed the need to have long-term solutions, for instance through integrating heat mitigation into urban planning, and systematically conducting post-heat evaluations to inform future actions.

Concluding the discussion, Kishore pointed to the importance of enhancing our collective and shared understanding of extreme heat, for instance, by developing heat rating systems that will enable global cooperation on the topic and help harmonize different assessments across different countries. “Extreme heat is a grave and big issue challenging our resilience. We need to appreciate the scale of this challenge and raise our level of ambition to match the scale,” he concluded.